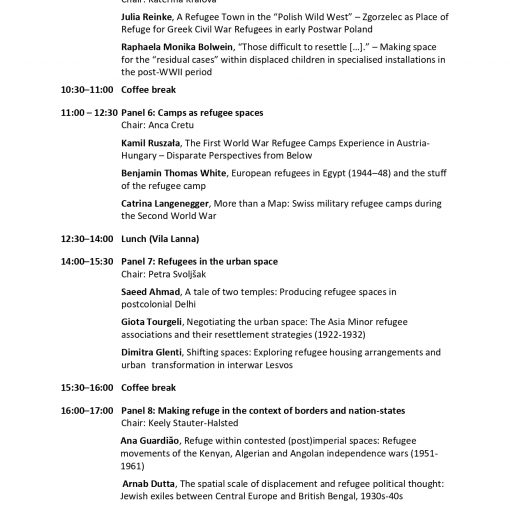

Several members of the Unlikely Refuge? team joined the 6th Congress on Polish Studies at the Technical University of Dresden (14-17 March 2024), forming a panel entitled “Poland as a Place of Refuge in the ‘Short’ 20th Century between Upheavals and New Beginnings”.

Still mostly known as a region producing flight and emigration, Poland has a history as a site and destination of refugee migration as well. In the ‘short’ 20th century, three “refugee moments” stand out as being closely connected to upheavals, but also to new beginnings:

The first took place in the context of World War I, when in the aftermath after a long time of post-partition statelessness, a new Polish state came into existence. Tasked with handling refugee flows, the emerging state by individual bureaucrats and informal practices also engaged in shaping citizenship and definitions of national identity.

World War II as the “most brutal rupture” caused Polish lands to become a site of immense flight migration, which was precisely characterized by the dissolution of state structures. Nevertheless, the refugee movement had to cope with the conditions of statelessness, relying on understudied informal local support networks and internal migrants’ own agency.

In the postwar years, after the “westward shift” of its borders, the new Polish state participated in a coordinated action of the emerging Eastern Bloc in hosting Greek and Macedonian refugees from the Greek Civil War. Mostly settled in the “recovered lands”, this refugee reception marked the new political positioning and constituted one arena of postwar reconstruction on Poland’s path to the new beginning of the “People’s Republic”.

With these three case studies focusing on crucial times of upheavals and new beginnings during the 20th century, this panel aims to acknowledge Poland’s role as a place of refuge and integrate Polish history with refugee studies.

Panellists

- Keely Stauter-Halsted, University of Chicago

- Lidia Zessin-Jurek, Masaryk Institute and Archives, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague

- Julia Reinke, Masaryk Institute and Archives, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague/ PhD candidate at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena

Discussant:

- Michal Frankl, Masaryk Institute and Archives, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague

Keely Stauter-Halsted: Refugeedom as Rupture and New Beginning: Return Migration and the Construction of Polish Citizenship after World War I

As the guns of World War One fell silent, some 2.5 million refugees, asylum seekers and evacuees gathered on Poland’s still undefined frontiers, seeking admission to the newly reborn republic. Constructed from the embers of three fallen empires, the post-Versailles Polish state was faced with the dual existential challenge of defending its territory from neighboring armies while sorting through the enormous and desperate population on its borders. How newly appointed government officials would treat this surge of migrants would help define both Poland’s civic institutions and the make-up of its future population. For the first time in the history of postwar repatriation, former residents were rigorously screened before returning to their factories and farms. This paper looks at the filtration process as both a disruption and a new beginning. It focuses on the shifting criteria used to assess incoming migrants as border guards sorted for contagious diseases, political disloyalty, and ethno-national difference, seeking to mold the biological content of the nascent state. At the same time, it addresses the ways the settled population challenged official decisions, seeking to write members of rejected groups back into the civic community. In the end, the presentation argues, border-making and refugee arbitration in the nascent Polish state helped shape a dynamic process of inclusion and exclusion that continued for the duration of the young republic’s existence. Far from functioning as a steadily narrowing aperture of belonging, Poland’s governing apparatus often incorporated the input of its wider settled population in making determinations about civic membership. The result was a heterogeneous community that retained lingering elements of diversity from imperial times, reflecting a slow transition from ethnic heterogeneity to ethno-national exclusion.

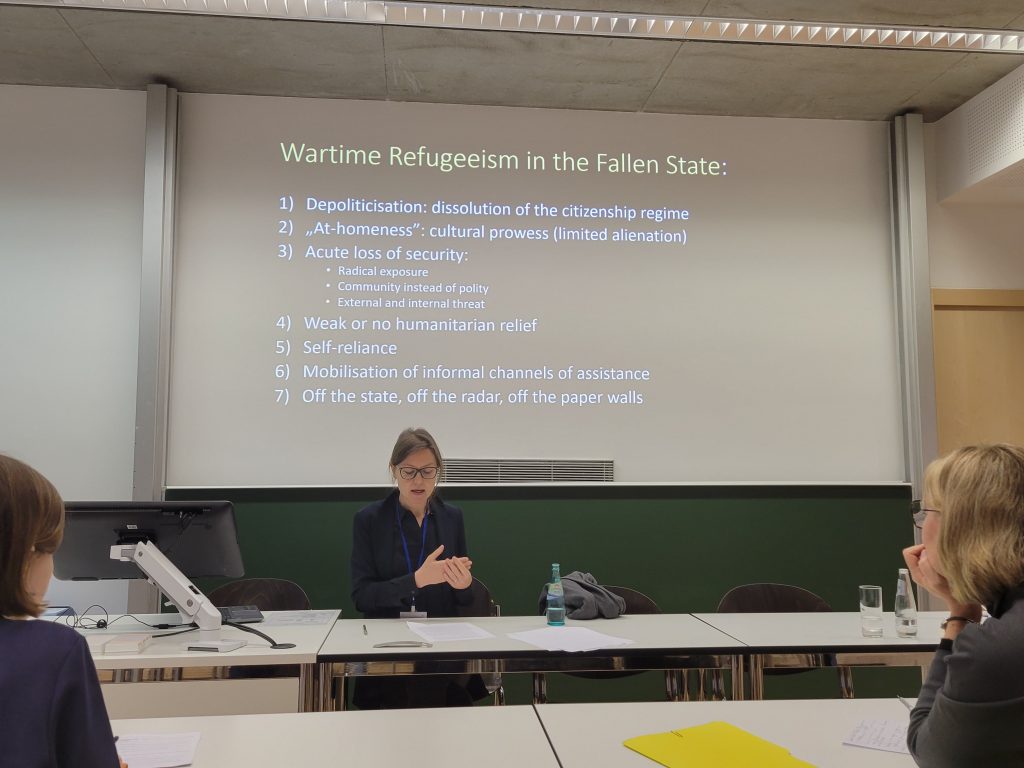

Lidia Zessin-Jurek: Refugees in Statelessness — the Fall of Poland in 1939

“Crowds of refugees felt like shipwrecked oarsmen on a raft amidst the raging waves and the wreckage of what had once borne a proud name” — this wreckage from Julius Margolin’s metaphor describes Poland in September 1939. Following the combined German and Soviet invasion the Polish (state)ship was disintegrating in plain sight. Poland rapidly lost its defensive and managerial power, as well as the infrastructural means on which this power rested. Based on the refugee voices, this paper focuses on crisis migration in the violent conditions of a collapsingor falling state under the pressure of war of aggression. It looks at the experience of refugees in successive short stages of the process of state collapse caused by external aggression, rather than internal decomposition: the chaos of warfare, the anarchy of the interregnum with the period of patchy statelessness until the moment of the rapid establishment of occupation regimes.

The paper examines the case in which the sovereign territory, underlying much of the law and normative conception of refugees, disappears. It provides a perspective on the refugee experience in a transitional situation of statelessness, in which the formal (state-centric) concept of the refugee is deconstructed and invites a reorientation. Indeed, this perspective contributes to the discussion on the limits of the legally constructed understanding of refugeeism — for this Polish case clearly demonstrates that the refugee experience begins with the involuntary need to abandon home, and is not dependent on the arbitrary criterion of a person crossing some border or being subject to some institutionalised migration policy.

Julia Reinke: Refugee Children from the Greek Civil War in the “Polish Wild West”. The “Recovered Territories” as Place of Refuge in Socialist Poland after World War II

When the Polish state was resurrected after World War Two, its borders had been significantly shifted westwards, entailing an immense population exchange in the postwar order. However, the new population in the so-called “recovered territories” was not only comprised of various groups of “repatriates”, ethnic minorities and local communities, but also of Greek and Macedonian refugees from the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) who were received there as of 1948 into the early 1950s. In providing refuge to these “fellow comrades” – defeated communist partisans, and with them a considerable number of children –, the new regime joined in a coordinated action of the Eastern Bloc, marking the new political positioning of the young “people’s democracy”.

This refugee reception, however, should not only be viewed as an expression of international solidarity – it itself embodied an arena where the new socialist order was to be established. This paper proposes a look at the implementation of care for the refugee children based mainly on regional and local sources. These allow for insights into everyday life issues and intersections between the refugees and the local context. How did these ‘prototype refugees’ to socialist Poland fit into the striving for ethnic Polish homogeneity in the aftermath of World War II? What conditions did the “Polish Wild West” (Beata Halicka) provide for their accommodation? This paper proposes an analysis especially of the refugee management on the ground, aiming at an integrated study of local structures against the background of the evolving socialist state.